High-Low Testing

High-low testing has changed the way I build software. When I first started using Rails five years ago, the paradigm of choice was fat model, skinny controller. This guidance is well-intentioned, but the more I worked within its bounds, the more frustrated I became. In particular, with fat models. Why should anything in software be fat?

Fat and complex models spread their entanglements likes roots of an aspen. When models adopt every responsibility, they become intertwined and cumbersome to work with. Development slows and happiness dwindles. The code not only becomes more difficult to reason about, but is more arduous to test. Developer happiness should be our primary concern, but when code is slow and poorly factored, we loosen our grasp on that ideal.

So how can we change the way we build software to optimize for developer happiness? There are a number of valuable techniques, but I’ve coalesced on one. The immediate win is a significantly faster unit test suite, running at thousands of tests per second. As a guiding principle, the implementation should not suffer while striving to improve testability. Further, though I’ll use Rails as an example, such a technique should be transferable to multiple domains, languages and frameworks.

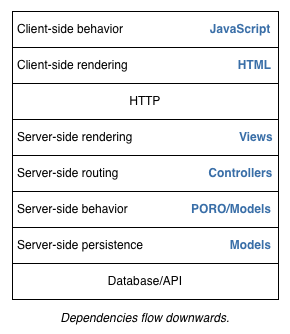

The approach I’m describing is what I call high-low testing. The name says it all; the goal is to test at a high, acceptance level and the low, unit level. The terms “high” and “low” come from the levels of test abstraction in an application. See the diagram below. In a web app, a higher test abstraction executes code that drives browser interactions. Lower test abstractions work with the pieces of logic that eventually compose a functioning system.

This article outlines the practices and generalized approaches to implementing high-low testing in Rails apps of any size. We’ll discuss the roadmap to fast tests and how this mindset promotes better object orientation. Hopefully after considering high-low testing, you’ll understand how to increase your developer happiness.

Aside: this article is broken into two major sections: the primary content and the appendix. Feel free to ignore the appendix, though it contains many real-world discussion points.

Seeking a better workflow

Before explaining how to apply high-low testing, let’s look at the driving forces behind it.

You may be working in a large legacy codebase. Worst case scenario, there are zero tests and the work you’re doing needs to build on existing functionality. Since the tests are either slow or nonexistent, you would like a rapid feedback cycle while adding new features. Or, you’re refactoring and need to protect against regressions. How do you improve the feedback cycle while working in a legacy codebase?

You may be working on a medium-sized app whose entire test suite could benefit from improved feedback cycles. You’ll incrementally move towards a high-low approach and continually reap the benefits along the way. How do you introduce high-low testing with the goal of easy maintainability as the app ages?

If you’re working with a greenfield app, you may not benefit immediately from high-low testing. It requires discipline and can potentially be detrimental to the code. Nonetheless, if you plan on maintaining the project for the long haul, you’ll see near constant test suite times and improved productivity. How do you apply high-low testing without inhibiting the software design?

Regardless of application size, our primary goal is to integrate a sane testing philosophy that doesn’t constrain the feedback-driven workflow we practice daily. Fast tests are great for building and refactoring, but we also want additional feedback mechanisms that highlight smells in our code.

Dependencies are a necessary evil

Developer happiness is important. When I’m unhappy, it’s likely due to intermingled dependencies or a deranged pair. I can’t fix crazy. Anyone who’s taken on a rescue project knows the first thing you do is upgrade dependencies (maybe the very first thing you do is write some tests.) As a first step, it’s also the most demoralizing because you don’t just “upgrade dependencies,” you trudge through the spaghetti, ripping things out, rewriting others, and you crawl out the other side in hopes that everything still works. This is an extreme case of exactly what happens in many Rails applications.

Dependencies are evil. I mean both third party dependencies and those you write yourself. Any time one piece of code depends on another, there’s an immediate contingency on maintaining the relationship. Realistically, there’s no way to remove all dependencies, not that you’d want to anyway. Building maintainable software is primarily about organizing dependencies so they don’t pollute each other. They’re a necessary and unavoidable evil, but left unkept, they’ll eventually erode the codebase.

With Rails in particular, it’s almost brainless to introduce dependencies. Just drop a line in the Gemfile. Or, just reference a constant by name. When the app needs it, it’s ready and available or is immediately autoloaded. Such dependency management propagates itself throughout the framework and the applications built on top. Most apps I’ve worked on buy into this convenience to maximize developer productivity, but this productivity boost early in a project becomes a hindrance as it comes of age.

Unsurprisingly, the problem with dependencies is much more prolific than loading the world via a Gemfile. It works its way through every aspect of every piece of software. Rails unfortunately encourages dependency coupling through eagerloading and reliance on the framework. The goal of high-low testing is to remove the discomfort of intermingled dependencies. The resulting code is often better factored, easier and faster to test, and more pleasurable to work with.

Getting started

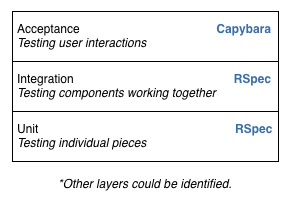

High-low testing is the practice of working at extreme poles in your test suite. You’ll work at the acceptance level to validate happy and questionable paths, and you’ll work at the lowest level possible, with the units of your code. See the below diagram. Most Rails applications test across all layers. The integration layer (and acceptance layer) tends to be slow because it’s evaluating many parts. When most of an application’s business logic is tied to Rails, it must be tested at the integration layer. Depending on your style, you may continue to test at the integration layer, but high-low testing promotes doing so without depending on Rails.

The end result is a full test suite composed of two main characteristics: a speedy unit suite for rapid feedback, and a slow acceptance suite to guard against regressions. I’ve found the ratio of acceptance to unit tests to be largely weighted towards unit tests. The more tests that can be pushed to the unit level, the more rapid and rewarding the development cycle. The unit level is the most interesting, so that’s the focus of this article, but let’s briefly look at testing high.

Testing high

Testing high means working at an acceptance level and driving the browser to verify most things are working as intended. You may cover around half of your application code with acceptance tests, but that’s OK, since you’ll also be writing unit tests to guard against the edge cases.

Acceptance testing can be done with any tool that drives the browser, but I prefer Capybara on Poltergeist.

In any project, using high-low testing or otherwise, acceptance tests should not exhaustively cover all possible use cases. It should cover basic cases, with further emphasis on features that provide high business value or expose risk. For instance, login and registration should be tested thoroughly, but testing validations on every form is superfluous.

Acceptance tests will always be slow. It’s the product of many layers of implementation working together to produce an anthropomorphic interaction with the software. While unit tests are much more akin to computer-computer interaction, acceptance tests give us an extra bit of confidence because they’re driving a real browser.

This extra bit of confidence goes a long way to building trust in your test suite, which is the primary reason we test in the first place. We must ensure the software works, with the goal of safe deployment when all dots are green. Few other forms of testing can induce such confidence, which is why acceptance tests are invaluable.

High level tests also execute the entire stack. Everything from the HTTP request, through the router, controller, model and database, and back up to the browser’s rendering engine. This is particularly important because acceptance tests can cover parts of the Rails stack that are painful to test. I’m looking at views and controllers.

A single Cucumber feature could cover multiple views and controllers. Testing high means covering pieces of the application that would otherwise burden a developer with excessive maintenance. Unit testing views and controllers introduces unnecessary test churn, so the bang for your buck with acceptance tests is enormous.

Really, high-low testing doesn’t change the way you write acceptance tests. Life carries on as usual. You may add some additional acceptance tests to guard against things that would otherwise be tested at the integration layer, but the style is largely the same. The significant changes to a traditional Rails testing approach come in the form of unit tests.

Testing low

Testing low means working at a unit level. When most people think about unit testing Rails apps, it often involves testing methods of models. By “models,” I’m referring to classes that inherit from ActiveRecord::Base. In a fat model/skinny controller setup, unit tests would definitely include models. But I avoid fat models like the plague. I want a fast testing environment that encourages better object orientation. To do this, we need to separate ourselves from Rails. It might seem extreme, but it’s the most successful way I’ve scaled projects with high complexity.

This all stems from the nature of dependencies. They (should) always flow downwards. Higher abstractions depend on lower abstractions. As a result, the most dependency-free code resides at the bottom of the stack. The closer we can push code into this dependency-free zone, the easier it is to maintain.

By decoupling our business logic from the framework, we can independently test the logic without loading the framework into memory. The acceptance suite continues to depend on the framework, but by keeping the unit suite separate from the acceptance suite, we can keep our units fast.

Let’s look at some code.

Consider an app that employed the fat model, skinny controller paradigm where all of our business logic resides in models inheriting from ActiveRecord::Base. Let’s look at a simple User class that knows how to concatenate a first and last name into a full name:

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

def full_name

[first_name, last_name].joins(' ')

end

end

And the tests for this class:

describe User do

describe '#full_name' do

user = User.new(first_name: 'Mike', last_name: 'Pack')

expect(user.full_name).to eq('Mike Pack')

end

end

What’s painful about this? Primarily, it requires the entire Rails environment be loaded into memory before executing the tests. Sure, early in a project’s lifetime loading the Rails environment is snappy, but this utopia fades quickly as dependencies are added. Additionally, tools like Spring are brash reactions to slow Rails boot times, and can introduce substantial complexity. The increasingly slow boot times are largely a factor of increasing dependencies.

High-low testing says to move methods out of classes that depend on Rails. What might traditionally fall into an ActiveRecord model can be moved into a decorator, for instance.

require 'delegate'

class UserDecorator < SimpleDelegator

def full_name

[first_name, last_name].joins(' ')

end

end

Notice how we’ve manually required the delegate library. We’ll investigate the benefits of this practice later in the article. The body of the #full_name method is identical, we really didn’t need to be anywhere close to Rails for this behavior.

The UserDecorator class would likely be instantiated within the controller, though it could be used anywhere in the application. Here, we allow the controller to prepare the User instance for the view by wrapping it with the decorator:

class UsersController < ApplicationController

def show

@user = UserDecorator.new(User.find(params[:id]))

end

end

Our view can then call @user.full_name to concatenate the first name with the last name.

The test for the UserDecorator class remains similar, with a couple differences. We’ll mock the user object and refer to our new UserDecorator class:

require 'spec_helper'

require 'models/user_decorator'

describe UserDecorator do

describe '#full_name' do

user = double('User', first_name: 'Mike', last_name: 'Pack')

decorator = UserDecorator.new(user)

expect(decorator.full_name).to eq('Mike Pack')

end

end

There are a few important things to note here. Again, we’re explicitly requiring our dependencies: the spec helper and the class under test. We’re also mocking the user object (using a double). This creates a boundary between the framework and our application code. Essentially, any time our application integrates with a piece of Rails, the Rails portion is mocked. In large applications, mocking the framework is a relatively infrequent practice. It’s also surprising how little the framework does for us. Compared to the business logic that makes our apps unique, the framework provides little more than helpers and conventions.

“Rails is a delivery mechanism, not an architecture.” – Uncle Bob Martin

It’s worth noting that mocking can be a powerful feedback mechanism. In the ideal world, we wouldn’t have to mock at all. But mocking in this instance tells us, “hey, there’s an object I don’t want to integrate with right now.” This extra feedback can be a helpful indicator when striving to reduce the touchpoints with the framework.

Requiring spec_helper is likely not new to you, but the contents of our new spec_helper will be. Let’s look at a single line from a default spec_helper, generated by rspec-rails:

require File.expand_path("../../config/environment", __FILE__)

This is the devil, holding your kitchen sink. This single line will load most of Rails, all your Gemfile dependencies, and all your eager loaded files. It’s the “magic” behind being able to freely access any autoloaded class within your tests. It comes with a cost: speed. This is the style of dependency loading that must be avoided. Favor fine-grained loading when speed is of the essence.

Here is what a baseline spec_helper would look like in a high-low setup. We require the test support files (helpers for our tests), we add the app/ directory to the load path for convenience when requiring classes in our tests, and we configure RSpec to randomly order the tests:

Dir[File.expand_path("../support/**/*.rb", __FILE__)].each { |f| require f }

$:.unshift File.expand_path("../../app", __FILE__)

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.order = "random"

end

Nothing more is needed to get started.

With this setup, you could be testing hundreds or thousands of classes and modules in sub-second suite times. As I’ve already expressed, the key is separating our tests from Rails. It turns out, most of the business logic in a typical Rails application is plain old Ruby. Rails provides some accessible helpers, but the bulk of logic can be brainlessly extracted into classes that are oblivious to the framework.

Isolating the framework

I want to be clear about something. For the purposes of this article, I’m referring to “integration tests” as those that utilize the framework. Integration means nothing more than two pieces working together, and integration testing is strongly encouraged. The style of integration testing that’s discouraged is that which integrates with the framework. I am not advocating that you mock anything but the framework. Heavy mocking has known drawbacks, and should be avoided.

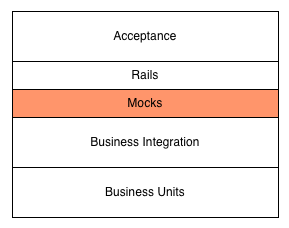

Mock only the pieces that rely on the framework. Integration between low-level business objects can often be safely tested in conjunction without mocking. What’s important is isolating the framework from the business logic. The below diagram illustrates this separation.

The important thing to take away from this diagram is that below the mocking layer, you can test in whatever style is most comfortable. If you want to test multiple objects as they execute in symphony, introduce an integration test. In the cases where you’re testing simple business rules that have no dependencies, unit test them normally. In either case, each file will explicitly require its dependencies.

If the mocking layer becomes cumbersome, additional tooling can be leveraged to more easily work with it. For instance, factory_girl can be used to encapsulate the data required of the mocks and separate the framework from the business logic. Notice this factory uses an OpenStruct instead of the implicit User class, which forms the moat needed to keep Rails out of the tests:

require 'ostruct'

FactoryGirl.define do

factory :user, class: OpenStruct do

first_name 'Mike'

end

end

By using OpenStruct, instances created by FactoryGirl will be basic OpenStruct objects instead of objects relying on Rails. We can use these surrogate factories as you would a normal factory:

it 'has a first name' do

expect(build(:user).first_name).to eq('Mike')

end

Example refactor to isolate the framework

This isolation from Rails encourages better object orientation. Let’s refactor a fat model into the more ideal high-low testing structure. The example below is inspired by an actual class in a large client project. I’ve rewritten it here for anonymity and brevity. The class encapsulates a cooking recipe. It performs two main behaviors:

- calculate the total calories in the recipe

- persist a value when someone favorites the recipe (using Redis::Objects)

class Recipe < ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :ingredients

has_many :foods, through: :ingredients

def total_calories

foods.map(&:calories).inject(0, &:+)

end

def favorite

Redis::Counter.new("favorites:recipes:#{id}").increment

end

end

A naive programmer would consider this sufficient. It works, right? There’s one argument I find compelling in favor of keeping it this way: “if I needed to find something about recipes, the Recipe model is the first place I’d look.” But this doesn’t scale with domain fragmentation and comprehension. At some point, the model contains many thousands of lines of code, becoming very tiresome to work with. Thousands of small classes with hundreds of lines of code each is much more comprehensible than hundreds of classes with thousands of lines of code.

An experienced programmer will instantly spot the problems with this class. Namely, it performs disparate roles. In addition to the hundreds of methods Rails provides through ActiveRecord::Base, it can also calculate the total calories for the recipe and persist a tangential piece of information regarding user favorites.

If the programmer were cognizant of high-low testing, their instincts would tell them there’s a better way to structure this code to enable faster and improved tests. As an important side effect, we also produce a more object-oriented structure. Let’s pull the core business logic out of the framework-enabled Recipe model and into their own standalone classes:

class Recipe < ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :ingredients

has_many :foods, through: :ingredients

def total_calories

CalorieCalculator.new(foods).total

end

def favorite

FavoritesTracker.new(self).favorite

end

end

By making this minor change, we gain a slew of benefits:

- The code is self documenting and easier to reason about without having to understand the underlying implementation.

- The multiple responsibilities of calculating the total calories or persisting favorites has been moved into discrete classes.

- The newly introduced classes can be tested in isolation of the Recipe class and Rails.

- Dependencies have been illuminated in require statements and inputs into methods.

Before this improvement, to test the #total_calories method, we were required to load Rails. After the refactor, we can test this logic in isolation. The original implementation calculated total calories from foods fetched through its has_many :foods association. Though not impossible, under test, it would have been nasty to calculate the total calories from something other than the association. In the below code, we see it’s quite easy to test this logic without Rails:

require 'spec_helper'

require 'models/calorie_calculator'

describe CalorieCalculator do

describe '#total' do

it 'sums the total calories for all foods' do

foods = [build(:food, calories: 50), build(:food, calories: 25)]

calc = CalorieCalculator.new(foods)

expect(calc.total).to eq(75)

end

end

end

The original code encouraged us to use the database to test its logic, which is unnecessary since the logic works purely in memory. The improved code breaks this coupling by making implicit dependencies explicit. Now, we can more easily test the logic without a database.

We’re one step closer to removing Rails from the picture; let’s realize this goal now. Everywhere that Recipe#total_calories was being called can be changed to refer to the new CalorieCalculator class. Similarly for the #favorite method. This refactor would likely be done in the controller, but maybe in a presenter object. Below, the new classes are used in the controller and removed from the model:

class RecipesController < ApplicationController

before_filter :find_recipe

def show

@total_calories = CalorieCalculator.new(@recipe.foods).total

end

def favorite

FavoritesTracker.new(@recipe).favorite

redirect_to :show

end

end

Now our Recipe class looks like this:

class Recipe < ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :ingredients

has_many :foods, through: :ingredients

end

An end-to-end test should be added to round out the coverage. This will ensure that the controller truly does call our newly created classes.

As you can see from the above example, high-low testing encourages better object orientation by separating the business logic from the framework. Our first step was to pull the logic out of the model to make it easier and faster to test. This not only improved testability but drove us towards a design that was easier to reason about.

Our second step reintroduced the procedural nature of the program. Logic flows downwards in the same sense that computers execute instructions sequentially. Large Rails models often contain significant amounts of redirection as models talk amongst each other. By moving our code back into the controller, we’ve reduced this redirection and exposed its procedural nature, making it easier to understand. As we continue through the article, we’ll look at even more ways high-low testing can improve the quality of a codebase.

Feedback, feedback, feedback

High-low testing is all about providing the right feedback at the right times. Do you need immediate feedback about application health as you work your way through a refactor? Keep your unit tests running on every change with Guard. Do you need a sanity check that everything is safe to deploy? Run your acceptance suite.

It’s been said many times by others, but feedback cycles are pertinent to productive software engineering. The goal of high-low testing is to provide quick feedback where you need it, and defer slow feedback for sanity checks. The shortcoming of many current Rails setups is they don’t delineate these two desires. Inevitably, everything eventually falls into the slow feedback cycle and it becomes increasingly difficult to recuperate.

Let’s look at how we can embrace short feedback cycles in applications of all sizes. Unless you’re curious, feel free to skip sections that don’t apply to your current projects. We’ll talk about working in legacy, middle-aged and greenfield applications.

Working with legacy codebases

The truth about legacy codebases is they will always be legacy. No matter how aggressively we refactor, there will always be a sense of technical debt. The goal is to eliminate future debt.

It’s easy to apply high-low testing principles to legacy codebases, but it’s done in addition to existing tests. If acceptance tests are already in place, continue to acceptance test in the prescribed fashion. If they’re not in place, begin adding them as new features are built. Backfilling tests for existing features is also a great step towards refactoring.

You won’t be able to immediately affect existing unit tests. These will require refactoring. But you can introduce new functionality as a suite that runs independent from any existing tests. To do so, create a new thin spec_helper, as described above, and begin requiring that instead of your normal spec_helper that loads Rails. You will now have three test suites:

- Your normal acceptance suite

- Your existing unit suite that loads Rails

- Your new unit suite that does not load Rails

So, how does it fit into your workflow? The way I’ve done it is to keep my Rails-less unit suite continuously running with Guard. New functionality will be tested in the new manner, and the rapid feedback cycles will be immediately beneficial.

Run your acceptance suite as you would normally, but break your unit tests into separate directories. my_app/spec/slow and my_app/spec/fast would be one way to accomplish this. You’ll then run your unit suites independently:

rspec spec/slow

rspec spec/fast

The latter should be run with Guard. If you want to run all units, just truncate the directory:

rspec spec

Of course, this will load the Rails environment and you’ll lose the benefits of speedy tests, but it can be done as a sanity check before a deploy, for instance.

The unit suite that requires Rails will continue to be slow, as will the acceptance tests. The slow unit suite will act as checks against regressions, much like the acceptance suite. The new, faster suite will keep you productive moving forward and act as a goalpost for refactorings. To maximize the benefits of the new suite, existing unit tests and code can be reengineered to use it. In the ideal sense, all units of code would be refactored away from Rails, but I won’t blow smoke up your ass.

Legacy codebases aren’t the most conducive to high-low testing but medium-sized codebases are a perfect fit. Let’s look at those next.

Working with medium-sized codebases

High-low testing feels most natural while working in semi-mature codebases which exhibit continual growth yet don’t feel bogged down by past decisions. The business domain within codebases of this size is well understood, which means the abstractions encouraged by high-low testing can be expressed easily. Further, while medium-sized codebases still progress regularly, there’s often enough time and resources to thoroughly consider design decisions for the sake of longevity.

To be clear, when I use the terms “legacy” and “medium-sized” codebases, I mean for them to be mutually exclusive. A medium-sized codebase can often feel legacy, but I’m referring to medium-sized codebases who have either employed high-low testing from the get-go or have refactored into a high-low testing paradigm.

As it pertains to medium-sized codebases, high-low testing exudes its worth ten times over. The ability to add functionality, refactor, and delete features becomes significantly faster than if a traditional fat model, skinny controller approach was taken. The primary benefit is, of course, the speed of the unit suite.

Consider the case where you’re asked to share a feature amongst varying but not dissimilar parts of an application, say billing. If originally the billing code was constructed to work in only one part of the app and now needs to be shared across multiple features, this would generally be considered a serious effort. If the test suite loads Rails, you could be looking at a 3-5 second delay every time the suite is run. Likely, these tests are also slow as they depend on many things and utilize sluggish and unnecessary IO-bound operations.

With high-low testing, hundreds or thousands of specs can be run in under a second with little to no boot time. The feedback is immediate. This is achieved exclusively by mocking slow dependencies. Mocking the database, API responses, file reads, and otherwise slow procedures keeps the suite fast.

Throughout a refactor, the test suite should always be a measure of progress. Normally, you begin by ripping out existing functionality, breaking a ton of tests. You sort of eyeball it from there and begin constructing the necessary changes. You update the code and the tests, and there’s a large degree of uncertainty. Don’t worry about proceeding while the tests are red. You’ll be red, and you’ll remain red until you’re done refactoring.

By continually running the test suite on every change (because it’s so fast), you’ll always have a sense of how far you’ve strayed. Are things breaking that you didn’t expect? Is the whole suite failing or only the related segments? Continually running the tests is an excellent reminder of the progress of your refactor. If you bite off too much, your tests are there to tell you. This rapid workflow is unachievable with most suites I’ve seen.

While high-low testing is a perfect match for medium-sized apps, it can and should be applied throughout the project’s lifetime. Let’s next look at the implications throughout an app’s inception.

Working with greenfield apps

Admittedly, high-low testing is not entirely natural in greenfield apps. It works best when the abstractions are well understood. In a greenfield app, the abstractions are often impossible to see. These apps are changing so rapidly that it would be more harmful to introduce an abstraction than to carry on blindly. Abstractions are generalizations of implementation. With rapid additions, the generalizations being made are full of folly.

But there is a way to apply high-low testing to such a situation, and it requires careful forethought and a bit of patience. The end result is almost always a better design and a stronger basis for refactoring. Let’s look at a situation where it’s difficult to see abstractions, and therefore difficult to decouple the framework from the business logic.

Say you’re building a blog, and you need to list all the posts. Using the Rails way, you’d find yourself constructing a query in a controller actions:

class PostsController < ApplicationController

def index

@posts = Post.published

end

end

Surely you either want to test that .published was called on Post or that .published returns the correct set which excludes unpublished posts. It feels awkward to abstract this single line into its own class. If you were to abstract it, what would you call the class? PostFinder? ViewingPostsService? You don’t yet have enough context to know where this belongs and what it will include in the future.

One might say you should extract it anyway under the assumption that it will shortly change. Since the unit tests are so fast, it will be an easy refactor. This is a fair assessment. I don’t have a silver bullet, but I will say this. Hold off on the abstraction. Don’t create another class, and don’t unit test this logic. Build a barebones acceptance test to cover this. A simple “the posts index page should have only published posts” acceptance test will often suffice. The point at which you better understand how this logic will change over time, extract it into its own class and write unit tests.

I’m still experimenting in this area, but I think it’s worth practicing to form a discipline and awareness of the implications. The goal, of course, is to find a healthy balance of introducing the right abstractions at the right time. With patience, high-low testing is an effective way of achieving that goal.

Ancillary feedback

Testing high-low exposes some fantastic ancillary benefits that sort of just fall into your lap. Foremost is the constant feedback from transparent dependency resolution.

In most Rails apps, you see a lot of code that utilizes autoloading. It’s a load-the-world approach that we’re trying to avoid. For instance, we may have one class that refers to another:

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

end

class WelcomeUserService

def send_email(id)

@user = User.find(id)

# Send the user an email

end

end

How did the WelcomeUserService class find the User class? Through conventions and a little setup, Ruby and Rails was able to autoload the User class on demand, as it was referenced. In short, Rails uses #const_missing to watch for when the User class is referenced, and dynamically loads it at runtime.

In the above example, there is no reason for the WelcomeUserService class to have to manually require the User class. This is a nice convenience, but imagine your class is growing over time and eventually autoloads 10 dependent classes. How will you know how many dependencies this class has? I’ll say it again, dependencies are evil.

With high-low testing, you’re removing yourself from Rails’ autoload behavior. You’ll no longer be able to benefit from autoloading, which is a good thing. If you can’t live without autoloading, you could construct your own autoloading setup, but I would encourage you to consider the following.

Every time you build a class or test disjunct from Rails, you must explicitly enumerate all of your requirements. The WelcomeUserService class would look more like this:

require 'models/user'

class WelcomeUserService

def send_email(id)

@user = User.find(id)

# Send the user an email

end

end

Notice we’re explicitly requiring the User class at the top. Any other dependencies would be required in a similar fashion. For our tests, we would also require the class under test:

require 'spec_helper'

require 'services/welcome_user_service'

describe WelcomeUserService do

...

end

This might appear to be a step backwards, but it’s most certainly not. Manually requiring your dependencies is another feedback mechanism for code quality. If the number of dependencies grows large for any given class, not only is it an eyesore, but it’s an immediate reminder that something may be awry. If a class depends on too many things, it will become increasingly difficult to setup for testing, and may be an indicator of too many responsibilities. Manually requiring dependencies keeps this in check.

In general, the more feedback mechanisms you can create around dependency coupling, the higher the object cohesion. Such feedback mechanisms encourage better object-oriented design.

Know thy dependencies

Through practicing this technique, one thing has become overwhelmingly apparent: working at the poles produces more dependency revealing code. That’s what creating fast tests is all about. If the dependencies are transparent, obvious and managed, building fast tests is simple. If a system’s unit tests avoid wandering towards higher abstractions, the dependencies can be managed.

What we’re really trying to do is wrangle dependencies in a way that doesn’t inhibit future growth. There are two options: boot-the-world style eager loading or independently requiring where necessary. In the interest of fast tests and providing additional feedback mechanisms, high-low testing encourages the latter.

Finding a balance

Testing high means you can feel confident that the individual pieces of your software are glued together and functional. This confidence goes a long way when you’re shipping to production multiple times per day. You’ll feel more comfortable in your own skin and vehemently reassured that the work you’re doing is productive.

Testing low means you can focus on the individual components that comprise the functional system. The rapid feedback mechanisms provided by high-low testing aid in forging well-crafted software. The speed of the unit suite can be a precious asset when refactoring or quickly check the health of the system. Fast tests that encourage better object-orientation helps release the endorphins needed to keep your team happy and stable.

Like everything else in software engineering, deciding whether to apply high-low testing is full of tradeoffs. When is the right time to create abstractions? How important are fast tests? How easy is it for the team to understand the goals? These are all highly relevant questions that each organization must discuss.

If a team decides to practice high-low testing, the benefits are invaluable. Near-instantaneous unit tests at scale, better object-oriented design, and a keen understanding of system dependencies are amongst the perks. Such perks can prevent code cruft, especially in larger codebases. Since the principles of high-low testing can be easily conveyed to others, it becomes a nice framework for discussion.

Even if the approaches discussed in this article don’t fit your style, the core concepts can be the foundation for further enlightenment. It may seem academic, but I will attest that over the past four years of applying high-low testing, I’ve found my code to be better factored and easier to maintain. Your mileage may vary, but with enough persistence, I believe most teams will largely prosper both in productivity and happiness.

This concludes the explanation of high-low testing, so feel free to finish reading. If you’d like to explore more real-world tradeoffs, please continue reading the following sections.

The Appendix — Some unanswered questions

This article has mostly outlined some high level details about high-low testing. We haven’t addressed many common issues and how to accomplish fast tests within the confines of a real project. Let’s address that now.

High-low is not a prescription

What’s being described here is not a prescription for success, but an outline for fast tests. Developer happiness is the primary goal. Applying these techniques to your codebase does not guarantee you will produce better object-oriented code. Though alone it will likely encourage better choices, additional architectural paradigms are required to create well-designed and maintainable code.

There are plenty such architectural paradigms that accomplish the goal of decoupling the application from the framework. Two such examples are DCI and hexagonal architecture. Other less-comprehensive examples can be found in this excellent article on decomposing ActiveRecord models. In this article, we’ve used decorators and service objects as examples of framework decoupling.

Why is testing Rails unique?

In just about all the apps I’ve worked on, I can say that I’ve felt happy testing only a handful. As a community growing out of it’s infancy, we’re beginning to realize that the prescribed testing patterns passed down from previous generations are inadequately accommodating the problems we’re facing today. Particularly, problems of scale. As compared to even five years ago, Rails has grown, dependencies have grown, apps have grown and teams have grown.

The same principles from the Java world we so vehemently defied are the only principles that will save this community. No, we don’t want Rails to become J2EE. Introducing new and impressionable blood to the Ruby world should be done in such a way that encourages ease of use. Ease of use often comes from few abstractions, which is why we’re here today.

Rails hates business abstractions. Coincidentally, framework abstractions are OK, like routing constraints. You’re encouraged to use three containers: models, views and controllers. Within those containers, you’re welcome to use concerns, which are a displacement of logic.

The problem is probably better described as frameworks who discourage abstractions. This is littered throughout Rails. Take, for example, custom validators. You’d think to yourself, “if this system is properly constructed, I’d be able to use standard validators in my custom validator.” You’d be partially right.

Let me show you an example. Say I want to use a presence validator in my custom validator:

class MyCustomValidator < ActiveModel::Validator

def validate(record)

validator = ActiveModel::Validations::PresenceValidator.new(attributes: [:my_field])

validator.validate(record)

end

end

This works, if you expect your model to be intrinsically tied to your validations. The above code will properly validate the presence of :my_field, but when the validation fails, errors will be added to the model. What if your model doesn’t have an errors field? The PresenceValidator assumes you’re working with an ActiveModel model, as if no other types of models exist. Not only that, but your model also needs to respond to various other methods, like #read_attribute_for_validation.

I want something more akin to this API:

class MyCustomValidator < ActiveModel::Validator

def validate(record)

validator = ActiveModel::Validations::PresenceValidator.new

validator.validate('A value') #=> true

validator.validate(nil) #=> false

validator.validate('') #=> false

end

end

There is no need for the PresenceValidator to be tied to ActiveModel, but it is and so are many other things in Rails. Everyone knows, if you don’t follow The Rails Way, you’ll likely experience some turbulence. Yes, there should be guidelines, it should not be the frameworks job to mandate how you architect your software.

Isn’t the resulting code harder to understand?

An argument could certainly be made to illustrate the deficiencies of code produced as a result of high-low testing. The argument would likely include rhetoric around a mockist style of testing. Indeed, a mockist style can certainly encourage some odd approaches, including dependency injection and superclass inheritance mocking.

These arguments are valid and exhibit important trade offs to weigh. However, if the mocking boundaries are well-defined and controlled, they can be minimized.

The most prominent mocking territory in high-low tested apps is the boundary between Rails and the application logic. In most large applications I’ve seen, the application logic comprises the majority of the system. The framework leverages the application on the web. It’s important to clearly define this boundary so that the framework does not bleed into the domain.

If this separation is properly maintained, the amount of additional mockist style techniques can be nonexistent, if desired. The application logic can be tested in a classical, mockist or other style, depending on the preferences of the team.

Don’t fall down the slippery slope

You may be inclined to load a single Rails dependency because you’re used to various APIs. ActiveSupport, for instance, contains some useful tools and you may feel inclined to allow your application to rely on such a library. Adding it seems harmless at first, but beware of the slippery slope of dependencies.

You might think to yourself, “adding ActiveSupport will add, what, 1 second to my test suite boot time?” And you may be correct. But when you consider that ActiveSupport comprises about 43K LOC or 37% of the entire Rails codebase as of 4.1.1, and that you’ll likely be using a very very small fraction of the packaged code, the tradeoffs feel far too imbalanced.

Instead, build your own micro-library to handle the conveniences you need. Maybe this request seems ludicrous, but I guarantee you’ll be surprised by how few methods you actually need from ActiveSupport. The tradeoff for speed is compelling and warranted.

What about validations, associations and scopes?

You have a few options, none of which are ideal.

Firstly, you shouldn’t be testing associations. Let’s be serious, if your associations aren’t in place, a lot is broken.

If you must test your validations because they’re complex or you don’t believe the single line it took to write it is enough of an assurance, one option is to test them at the acceptance level. This is a slow means of verifying validations are in place, but it is effective:

Scenario: User signs up with incomplete data

Given I am on the registration page

When I press "Submit"

Then I should see "Username can't be blank"

And I should see "Email can't be blank"

Slow and cumbersome, but effective.

If you’re testing a complex validation, it’s probably best to move the validation into a designated ActiveModel::Validator class. Since this class depends on Rails, you’ll need to compose some objects so Rails isn’t loaded within your tests. It works well to have a mixin that does the true validation, which gets included in your ActiveModel::Validator class:

module ComplexValidations

def validate(record)

record.errors[:base] = 'Failed validations'

end

end

This would be mixed into the validator:

class ComplexValidator < ActiveModel::Validator

include ComplexValidations

end

Testing the mixin doesn’t require Rails:

require 'spec_helper'

require 'validations/complex_validations'

describe ComplexValidations do

let(:validator) do

Class.new.include(ComplexValidations).new

end

it 'validates complexities' do

errors = {}

record = double('AR Model', errors: errors)

validator.validate(record)

expect(errors[:base]).to eq('Failed validations')

end

end

Another technique, and my preferred approach, is to introduce a third suite, similar to an existing unit suite in a legacy codebase. The third suite would live exclusively for testing things of this nature and comprised of slow unit tests. Of course, this suite should not be continually run with Guard, but will exist for situations that need it, like testing validations, associations and scopes. Be careful though, this introduces a slippery slope that makes it easy to neglect high-low testing and throw everything into the slow unit suite.

Scopes are tricky because they do contain valuable business logic that does warrant tests. Just like validations, verifying scopes can be moved to the acceptance level, but my recommended approach is to introduce a slow unit suite to test these.

If like me, you cringe at the thought of introducing a slow unit suite, one option is to stub the scopes. Set up a mixin like the previous example and use normal Rails APIs:

module PostScopes

def published

where(published: true)

end

end

When testing, just assert that the correct query methods are called:

describe PostScopes do

subject do

Class.new.extend(PostScopes)

end

describe '.published' do

it 'queries for published posts' do

expect(subject).to receive(:where).with(published: true)

subject.published

end

end

end

More complex mocking is necessary if the scope performs multiple queries:

def latest

where(published: true).order('published_at DESC').first

end

describe '.latest' do

it 'queries for the last published post' do

relation = double('AR::Relation')

expect(subject).to receive(:where).with(published: true).and_return(relation)

expect(relation).to receive(:order).with('published_at DESC').and_return(relation)

expect(relation).to receive(:first)

subject.latest

end

end

This level of mocking is too aggressive for my taste, but it works and allows for all the convenient scoping behavior we’re used to. It’s a little brittle, but damn fast.

11 comments