Component-Based Acceptance Testing

Have you heard of page objects? They’re awesome. I’ll refer to them as POs. They were conceived as a set of guidelines for organizing the actions a user takes within an application, and they work quite well. There are a few shortcoming with POs, however. Namely, the guidelines (or lack thereof) around how to handle pieces of the app that are shared across pages. That’s where components are useful.

A component is a piece of a page; a full page is comprised of zero or more components. Alongside components, a page can also have unique segments that do not fit well into a component.

On the modern web, components are more than a visual abstraction. Web components are increasing in usage as frameworks like Angular, Ember and React advocate their adoption to properly encapsulate HTML, CSS and JavaScript. If you’re already organizing your front-end code into components, this article will feel like a natural fit. Uncoincidentally, the behavioral encapsulation of components within acceptance tests is often the same behavioral encapsulation of components in the front-end code. But I’m getting a little ahead of myself…

Let’s quickly recap POs. POs date back to 2004, when originally called WindowDrivers. Selenium WebDriver popularized the technique under the name Page Objects. Martin Fowler wrote about his latest approach to POs in 2013. There’s even some interesting academic research on the impacts of POs. Generally speaking, a single PO represents a single page being tested. It knows the details of interacting with that page, for example, how to find an element to click.

Acceptance tests have two primary categories of events: actions and assertions. Actions are the interactions with the browser. Assertions are checks that the browser is in the correct state. The community prefers that POs perform actions on the page, yet do not make assertions. Assertions should reside in the test itself.

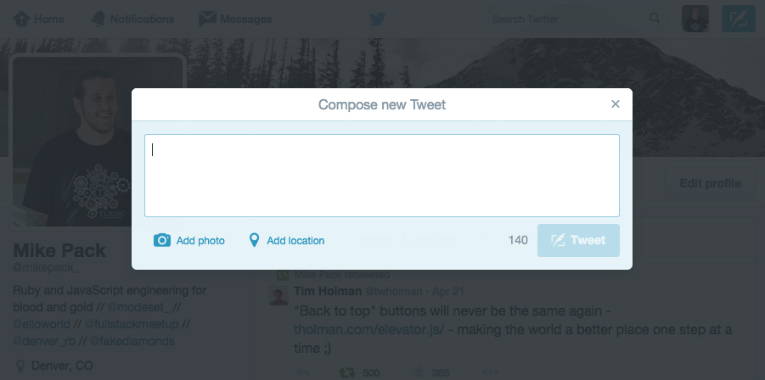

To demonstrate POs and components, let’s write some acceptance tests around a couple basic interactions with Twitter’s profile page, pictured below.

When clicking the blue feather icon on the top right, it opens a dialog that allows the user to compose a tweet.

For this demonstration, we’ll use Ruby, RSpec and Capybara to mimic these interactions in our acceptance tests, but the rules we’ll discuss here can be readily translated to other toolsets.

We might start with a PO that looks like the following. This simple PO knows how to visit a profile page, navigate to a user’s followers, and begin composing a tweet.

module Page

class Profile

include Capybara::DSL

def navigate(handle)

visit "/#{handle}"

end

def navigate_to_followers

click_link 'Followers'

end

def open_tweetbox

click_button 'Tweet'

end

end

end

The following test uses each part of the above PO.

describe 'the profile page' do

let(:profile_page) { Page::Profile.new }

before do

profile_page.navigate('mikepack_')

end

it 'allows me to navigate to the followers page' do

profile_page.navigate_to_followers

expect(current_path).to eq('/mikepack_/followers')

end

it 'allows me to write a new tweet' do

profile_page.open_tweetbox

expect(page).to have_content('Compose new Tweet')

end

end

That’s pretty much all a PO does. For me, there are a few outstanding questions at this point, but we’ve largely showcased the pattern. To highlight where POs start breaking down, let’s model the “followers” page using a PO.

module Page

class Followers

include Capybara::DSL

def navigate(handle)

visit "/#{handle}/followers"

end

def navigate_to_tweets

click_link 'Tweets'

end

# Duplicated from Page::Profile

def open_tweetbox

click_button 'Tweet'

end

end

end

Uh oh, we’ve encountered our first problem: a user can create a tweet from both the main profile page and from the followers page. We need to share the #open_tweetbox action between these two pages. The conventional wisdom here is to create another “tweetbox page”, like the following. We’ll move the #open_tweetbox method into the new PO and out of the other POs, and rename it to #open.

module Page

class Tweetbox

include Capybara::DSL

def open

click_button 'Tweet'

end

end

end

Our test for the profile page now incorporates the new Tweetbox PO and our code is a whole lot more DRY.

describe 'the profile page' do

let(:profile_page) { Page::Profile.new }

let(:tweetbox_page) { Page::Tweetbox.new } # New code

before do

# Original setup remains the same

end

it 'allows me to navigate to the followers page' do

# Original test remains the same

end

it 'allows me to write a new tweet' do

tweetbox.open

expect(page).to have_content('Compose new Tweet')

end

end

We’re now up against another conundrum: if both the tweets page and the followers pages have the ability to compose a new tweet, do we duplicate the test for composing a tweet in both pages? Do we put it in one page and not the other? How do we choose which page?

This is where components enter the scene. In fact, we almost have a component already: Page::Tweetbox. I dislike the conventional wisdom to make any portion of a page another PO, like we did with Page::Tweetbox. In my opinion, POs should represent full pages. I believe that whole pages and portions of pages (ie components) carry significantly different semantics. We should treat POs and components differently, even though their implementations are mostly consistent. Let’s talk about the differences.

Here are my guidelines for page and component objects:

- If it’s shared across pages, it’s a component.

- Pages have URLs, components don’t.

- Pages have assertions, components don’t.

Let’s address these individually.

If it’s shared across pages, it’s a component.

Let’s refactor the Page::Tweetbox object into a component. The following snippet simply changes the name from Page::Tweetbox to Component::Tweetbox. It doesn’t answer a majority of our questions, but it’s a necessary starting place.

module Component

class Tweetbox

include Capybara::DSL

def open

click_button 'Tweet'

end

end

end

In the tests, instead of using the sub-page object, Page::Tweetbox, we would now instantiate the Component::Tweetbox component.

Pages have URLs, components don’t.

This is an important distinction as it allows us to build better tools around pages. If we have a base Page class, we can begin to support the notion of a URL. Below we’ll add a simple DSL for declaring a page’s URL, a reusable #navigate method, and the ability to assert that a page is the current page.

class Page

# Our mini DSL for declaring a URL

def self.url(url)

@url = url

end

# We're supporting both static and dynamic URLs, so assume

# it's a dynamic URL if the PO is instantiated with an arg

def initialize(*args)

if args.count > 0

# We're initializing the page for a specific object

@url = self.class.instance_variable_get(:@url).(*args)

end

end

# Our reusable navigate method for all pages

def navigate(*args)

page.visit url(*args)

end

# An assertion we can use to check if a PO is the current page

def the_current_page?

expect(current_path).to eq(url)

end

private

# Helper method for calculating the URL

def url(*args)

return @url if @url

url = self.class.instance_variable_get(:@url)

url.respond_to?(:call) ? url.(*args) : url

end

include Capybara::DSL

end

Our profile and followers POs can now use the base class we just defined. Let’s update them. Below, we use the mini DSL for declaring a URL at the top. This DSL supports passing lambdas to accommodate a PO that has a dynamic URL. We can remove the #navigate method from both POs, and use the one in the Page base class.

The profile page, refactored to use the Page base class.

class Page::Profile < Page

url lambda { |handle| "/#{handle}" }

def navigate_to_followers

click_link 'Followers'

end

end

The followers page, refactored to use the Page base class.

class Page::Followers < Page

url lambda { |handle| "/#{handle}/followers"}

def navigate_to_tweets

click_link 'Tweets'

end

end

Below, the test now uses the updated PO APIs. I’m excluding the component test for creating a new tweet, but I’ll begin addressing it shortly.

describe 'the profile page' do

let(:profile_page) { Page::Profile.new }

before do

profile_page.navigate('mikepack_')

end

it 'allows me to navigate to the followers page' do

profile_page.navigate_to_followers

expect(Page::Followers.new('mikepack_')).to be_the_current_page

end

end

There are a few things happening in the above test. First, we are not hardcoding URLs in the tests themselves. In the initial example, the URL of the profile page and the URL of the followers page were hardcoded and therefore not reusable across tests. By putting the URL in the PO, we can encapsulate the URL.

Second, we’re using the URL within a profile_page PO to navigate to the user’s profile page. In our test setup, we tell the browser to navigate to a URL, but we only specify a handle. Since our Page base class supports lambdas to generate URLs, we can dynamically create a URL based off the handle.

Third, we assert that the followers page is the current page, using a little RSpec magic. When making the assertion #be_the_current_page, RSpec will call the method #the_current_page? on whatever object the assertion is being made on. In this case, it’s a new instance of Page::Followers. #the_current_page? is expected to return true or false, and our version of it uses the URL specified in the PO to check against the current browser’s URL. Below, I’ve copied the relevent code from the Page base class that fulfills this assertion.

def the_current_page?

expect(current_path).to eq(url)

end

This is how we can provide better URL support for POs. Naturally, portions of a page do not have URLs, so components do not have URLs. (If you’re being pedantic, a portion of a page can be linked with a fragment identifier, but these almost always link to copy within the page, not specific functionality.)

Pages have assertions, components don’t.

The conventional wisdom suggests that POs should not make assertions on the page. They should be used exclusively for performing actions. Having built large systems around POs, I have found no evidence that this is a worthwhile rule. Subjectively, I’ve noticed an increase in the expressivity of tests which make assertions on POs. Objectively, and more importantly, is the ability to reuse aspects of a PO between actions and assertions, like DOM selectors. Reusing code between actions and assertions is essential to keeping the test suite DRY and loosely coupled. Without making assertions, knowledge about a page is not well-encapsulated within a PO and is strewn throughout the test suite.

But there is one aspect of assertion-free objects that I do embrace, and this brings us back around to addressing how we manage components.

Components should not make assertions. Component objects must exist so that we can fully test our application, but the desire to make assertions on them should lead us down a different path. The following is an acceptable use of components, as we use it to perform actions exclusively. Here, we assume three methods exist on the tweetbox component that allow us to publish a tweet.

describe 'the profile page' do

let(:profile_page) { Page::Profile.new }

let(:tweetbox) { Component::Tweetbox.new }

before do

profile_page.navigate('mikepack_')

end

it 'shows a tweet immediately after publishing' do

# These three actions could be wrapped up into one helper action

# eg #publish_tweet(content)

tweetbox.open

tweetbox.write('What a nice day!')

tweetbox.submit

expect(profile_page).to have_tweet('What a nice day!')

end

end

In the above example, we use the tweetbox component to perform actions on the page and the profile PO to make assertions about the page. We’ve introduced a #have_tweet assertion that should know in which part of the page to find tweets and scope the assertion to that DOM selector.

Now, to showcase how not to use components, we just need to revisit our very first test. This test makes assertions about the contents of the tweetbox component. I’ve copied it below for ease of reference.

describe 'the profile page' do

let(:profile_page) { Page::Profile.new }

before do

profile_page.navigate('mikepack_')

end

it 'allows me to write a new tweet' do

profile_page.open_tweetbox

expect(page).to have_content('Compose new Tweet')

end

end

After converting this test to use the tweetbox component, it would look like the following.

describe 'the profile page' do

let(:profile_page) { Page::Profile.new }

let(:tweetbox) { Component::Tweetbox.new }

before do

profile_page.navigate('mikepack_')

end

it 'allows me to write a new tweet' do

tweetbox.open

expect(tweetbox).to have_content('Compose new Tweet')

end

end

Not good. We’re making an assertion on the tweetbox component.

Why not make assertions on components? Practically, there’s nothing stopping you, but you’ll still have to answer the question: “of all the pages that use this component, which page should I make the assertions on?” If you choose one page over another, gaps in test coverage will subsist. If you choose all pages that contain that component, the suite will be unnecessarily slow.

The inclination to make assertions on components stems from the dynamic nature of those components. In the case of the tweetbox component, pressing the “new tweet” button enacts the dynamic behavior of the component. Pressing this button shows a modal and a form for composing a tweet. The dynamic behavior of a component is realized with JavaScript, and should therefore be tested with JavaScript. By testing with JavaScript, there is a single testing entryway with the component and we’ll more rigidly cover the component’s edge cases.

Below is an equivalent JavaScript test for asserting the same behavior as the test above. You could use Teaspoon as an easy way to integrate JavaScript tests into your Rails environment. I’m also using the Mocha test framework, with the Chai assertion library.

describe('Twitter.Tweetbox', function() {

fixture.load('tweetbox.html');

beforeEach(function() {

new Twitter.Tweetbox();

});

it('allows me to write a new tweet when opening the tweetbox', function() {

$('button:contains("Tweet")').click();

expect($('.modal-title').text()).to.equal('Compose new Tweet');

});

});

By testing within JavaScript, we now have a clear point for making assertions. There is no more confusion about where a component should be tested. We continue to use components alongside POs to perform actions in our acceptance suite, but we do not make assertions on them. These tests will run significantly faster than anything we attempt in Capybara, and we’re moving the testing logic closer to the code under test.

Wrapping up

Unsurprisingly, if you’re using web components or following a component-based structure within your HTML and CSS, component-based acceptance testing is a natural fit. You’ll find that components in your tests map closely to components in your markup. This creates more consistency and predictability when maintaining the test suite and forges a shared lexicon between engineering teams.

Your mileage may vary, but I’ve found this page and component structure to ease the organizational decisions necessary in every acceptance suite. Using the three simple guidelines discussed in this article, your team can make significant strides towards a higher quality suite. Happy testing!

2 comments