Fixed Timeline, Variable Scope — Part Two

This is Part Two of a three-part series on fixed timeline projects — a faster, leaner, and more reliable way to ship high-impact innovation work.

In Part One, I argued that fixed timelines help control runaway scope, lead to better results, and leave teams more satisfied. They shift focus from output to outcomes, and give teams the structure to optimize for impact.

Now let’s get tactical.

In this installment, I’ll show how fixed timelines actually work, using a real, high-stakes project as an example. You’ll see how to define appetite, shape scope, and create a plan that drives results.

In Part Three, I’ll share six years of hard-earned lessons. What worked in the real world, what didn’t, and how to make fixed timelines sustainable.

Optimizing for Impact

Too many companies burn millions of dollars building production-grade software no one wants, not even the company itself.

Not because the final product is wrong, but because the execution is. In innovation work, top-down direction is a trap. Executives over-specify solutions, assuming their broad view equates to deep insight. It doesn’t.

The truth? Most executives aren’t close enough to the product. They miss the nuance in user motivations, edge cases, and constraints. That knowledge lives with the teams building it.

If you want impact, let your teams lead. Executives should define the problem, set the vision, and sketch boundaries of feasibility. Then get out of the way.

“It doesn’t make sense to hire smart people and then tell them what to do.” — Steve Jobs

The rest of this article assumes that culture exists. If your teams aren’t empowered to own solutions, this won’t work. But if they are, it’s time to talk about how to set up fixed timeline projects.

Project Lifecycle

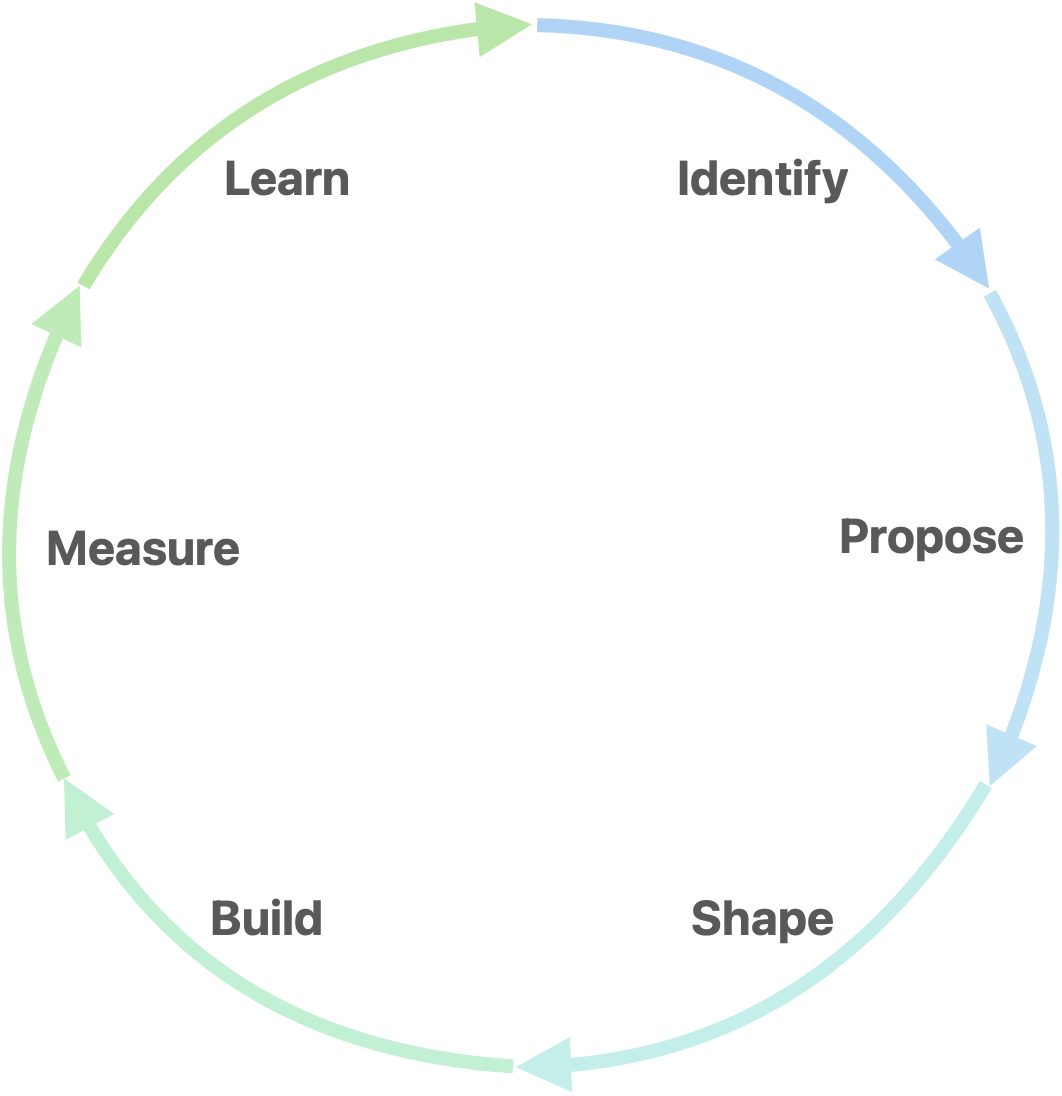

A healthy project lifecycle looks like this:

- Identify: Executives identify the most critical business problems

- Propose: Product and exec teams propose actionable problem areas

- Shape: Product and engineering teams “shape” problems into potential solutions

- Build: Engineering teams build and measure

- Measure: Data becomes product insights

- Learn: Insights become business knowledge

This model pushes problem-solving down to the teams closest to the product and turns learnings into a feedback loop for the business. Executives measure efficacy of their teams by their ability to produce outcomes for the business.

Fixed timelines reinforce this by being outcome-oriented, not output-obsessed. A project might look like:

“We’ll spend 4 weeks trying to reduce [X metric] by [Y%].”

Not:

“Our velocity will be X points.”

Output doesn’t matter if the outcomes aren’t met.

In this article, we’ll focus on steps 1–3: the planning phase. The rest — build and maintain — matter deeply, but they’re not today’s topic.

Plan Slow, Act Fast

Most companies get this backwards: they rush planning and overspend on building.

Planning is cheap. You can sketch wireframes, test ideas, and talk to customers without writing a line of production code. But once you deploy code, write documentation, or set customer expectations, everything gets expensive.

A core tenet of fixed timeline projects is this: building time is fixed, planning time is not. That’s the inverse of most company processes. The goal is to invest enough upfront so that the build phase can move fast and stay focused.

The book How Big Things Get Done drives home this point: plan slow, act fast.

Planning isn’t about locking in every detail, it’s about preparing for uncertainty. Think of it like planning a wedding. The date is fixed, and your job is to avoid disaster. You don’t try to control the weather or micro-manage the DJ’s playlist. Something will go wrong, embrace it.

Let’s look at a real example of a plan that struck the right balance. It has enough structure to move fast, but flexible enough to adapt. We’ll unpack its components in the sections ahead.

A Real Project

Healthcare businesses that offer live clinical services face a familiar problem: patients book appointments but don’t always show up.

They cancel at the last minute or disappear entirely.

That’s bad for business. A provider is still paid to be available, but with no one to treat, the time is lost. The company takes a double hit: a sunk cost and lost revenue.

This project aimed to solve that. The goal: reduce late cancellations and no-shows to improve margins and boost revenue.

The Appetite

This project had three things going for it:

- High impact: 30% of appointments were either late-canceled or missed entirely, double the industry standard. The business was eager to invest.

- Diminishing returns: The industry benchmark was 15%, so gains would get harder the closer we got.

- Uncertainty: It wasn’t clear how to close that gap.

Given the stakes, the shaping team proposed a 4-week appetite for 4 engineers.

The Project Spec

Every project needs a reference doc, a project spec.

It includes the problem statement, success criteria, and a rough plan. It’s the main output of the planning phase, and a prerequisite to start the build. Share it across the business to gather feedback, then finalize it with executive approval.

Here’s a lightly simplified version of the real spec from this project:

Problem: the business is losing revenue from missed appointments. Vision: Patients either show up or cancel in time to rebook their slot. Success Criteria: Reduce late cancellations and no-shows by 10%, as measured by our appointment completion metrics.

Scopes:

- [P0] Send email reminders before appointment

- [P0] Communicate cancellation policy during booking

- [P1] Offer more short-term booking availability

- [P1] Send text reminders on same cadence as email

- [P2] Let patients reschedule or cancel via text

- [P2] Draft a waitlist system plan

Wireframes:

- Reminder emails

- Booking flow UI changes

That’s all a smart, cross-functional team needs to start building, especially when backed by a clear strategy.

The scopes reflect the engineering estimates, but those estimates don’t dictate timelines.

This project started with a problem and everything else flowed from there. Let’s walk through how that happened.

Planning

Planning should be cheap.

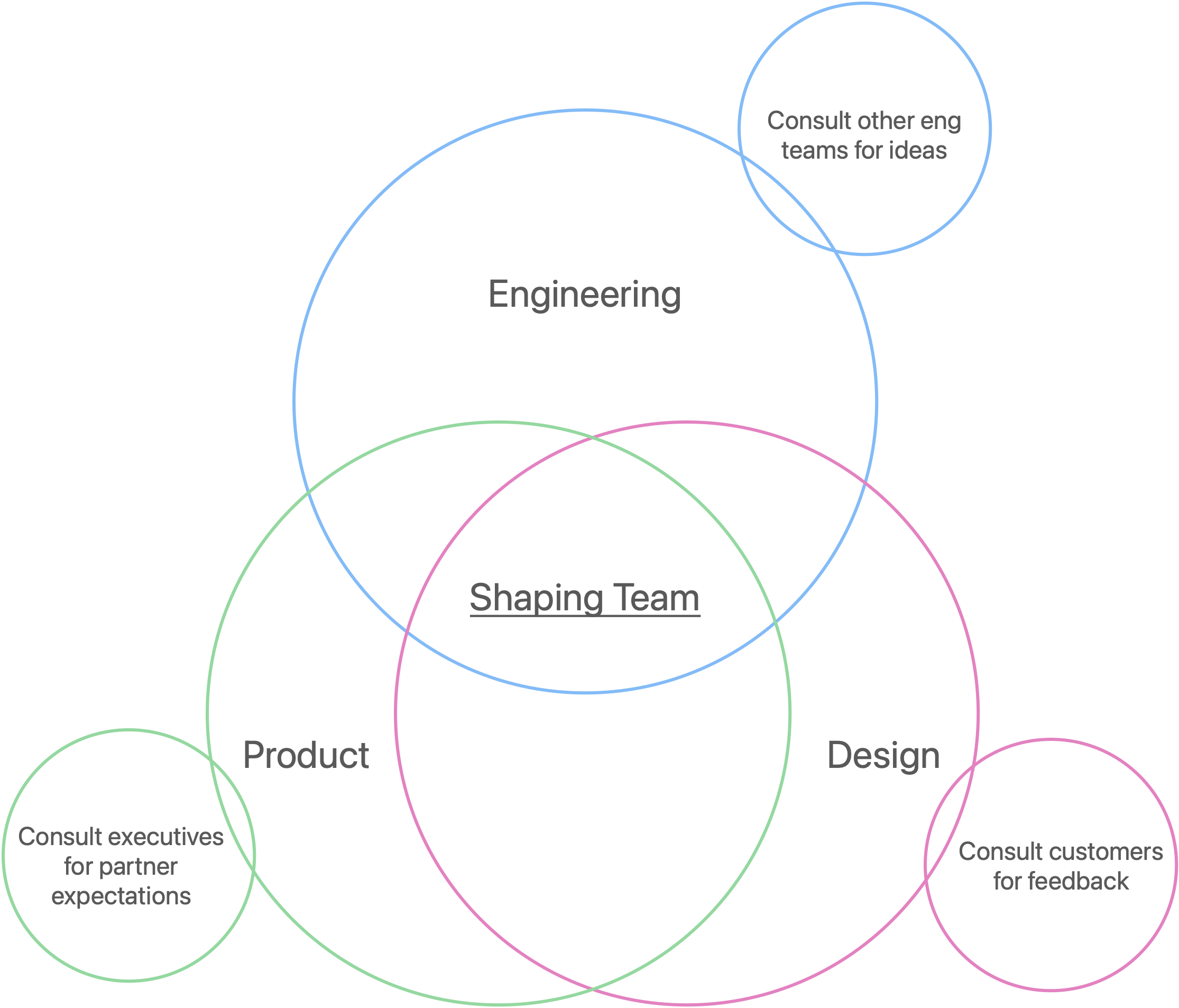

A small, senior “shaping team” leads the effort. Their job: create a spec that outlines the problem, success criteria, and a rough plan, without locking in long-term commitments.

The shaping team usually includes one person each from product, engineering, and design. It may include other critical members, and they are encouraged to consult executive sponsors, external partners, customers, or other internal teams.

Ideally, this same group leads the build phase. They’ve built context and trust, they’re best equipped to carry it forward.

The shaping phase is all about answering three questions:

- What’s our appetite?

- What’s our success criteria?

- What’s our rough plan (the scopes)?

Once confidence is high enough we’ve answered the above questions, the project can move onto the roadmap. Shaping doesn’t need to be done to get on the roadmap, just enough momentum to move forward.

Planning is “done” when the team is 80% confident nothing catastrophic will happen. That’s usually enough to start.

To gauge project readiness I like to ask things like:

“How confident are you the team knows how to build this?” “How confident are you these solutions will meet the success criteria?” “How confident are you this meets security and compliance requirements?”

Confidence scores are powerful. They compress diverse intuition into a shared signal. If scores are low, dig deeper. If they’re high, you’re close.

The goal is alignment and readiness, not perfection.

Find Your Appetite

Before you roadmap, you need to set your appetite: how much time, energy, and team bandwidth you’re willing to invest. Executives should help set the appetite because it reflects business priorities and forces tradeoffs.

Two things define appetite:

- How much time the business is willing to invest

- The size of the engineering team assigned

Appetite should reflect the value, risk, and clarity of the problem. A high-impact but uncertain opportunity? That might be worth 6 weeks and a full team. A well-defined tweak? Maybe just 2 weeks and a couple engineers.

“We believe this problem is worth solving, and we’re willing to spend this much to solve it.”

Appetite is not scope, it’s the investment boundary. It’s how long the team gets to explore a solution. It should be long enough to make a meaningful impact, but short enough to maintain urgency.

I’ve found 4 weeks is the sweet spot. Longer than that, and it becomes hard to hold a shared picture of the end goal. More than 6 weeks? That’s too uncertain, break it into phases.

Use these as directional levers:

- Increase it for high-value bets, complex integration work, or unproven technical foundations.

- Decrease it for repeatable solutions, vague metrics, or early-stage teams still learning this method.

Team size affects output volume, so match it to the appetite. It should be large enough to succeed, but small enough to avoid coordination drag.

In the next section, I’ll show how this appetite drives the roadmap, and why that makes fixed timeline planning so powerful.

Roadmapping

All you need to roadmap a project is the appetite. If the other elements are still being shaped, that’s okay.

Fixed timeline roadmapping is fast and predictable. Since the length of each project is known up front, you’re just slotting them into the calendar to align with business priorities.

This predictability is what lets senior leaders sleep at night. A roadmap block for a fixed timeline project will last exactly as long as the appetite; no more, no less.

Contrast that with fixed scope projects: roadmap blocks are based on estimates. And as we all know, they’re usually wrong.

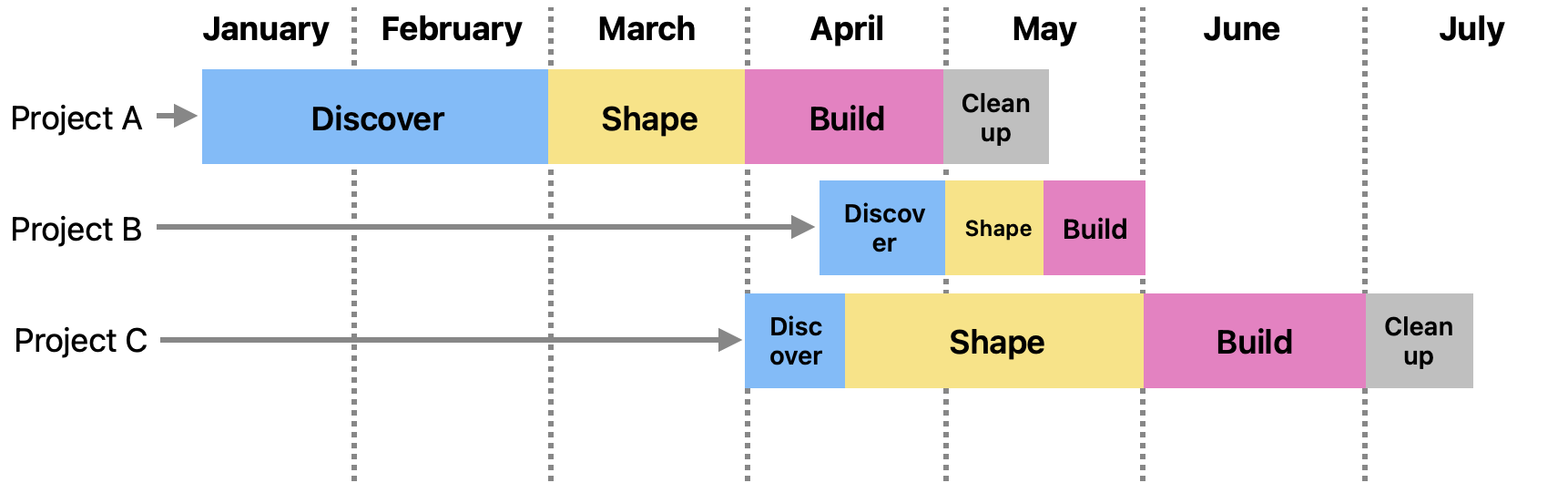

Here’s an example roadmap:

A roadmap for fixed timeline work should reflect more than just the build phase. Here’s a typical flow: 1. Discover: Product teams identify problems based on executive direction 2. Shape: Product and engineering teams propose solutions 3. Build: The team commits to building within the fixed timeline 4. Cleanup: Post-launch polish: bugs, refactors, etc.

Including all four phases gives the business visibility into everything the team’s juggling, not just the coding time.

Each phase can vary based on the project:

- Project A: Vague problem; long discovery, moderate shaping, standard build

- Project B: Clear problem and solution; fast discovery and shaping, straightforward build

- Project C: Clear problem, but complex solution; short discovery, long shaping and build

There’s lot of flexibility in roadmapping these projects. As long as the build phases don’t overlap, and depending on the size of your team, things can be shuffled around. Shaping phases can overlap if people can multitask. Discovery can run in the background or spike as needed.

Fixed timeline methodology is outcome-driven, which creates healthy pressure. There’s no rollover. Once time is up, the project ends.

That makes focus critical. Teams must say no to distractions and deprioritize incoming noise. The goal is simple: hit the success criteria within the timebox.

Defining Success Criteria

Success criteria should be grounded in two things:

- A problem statement – a clear articulation of what’s broken

- A vision – a picture of what it looks like once it’s fixed

The problem defines what we’re tackling. The vision defines what success looks like.

A sharp problem statement anchors the work in truth. It reflects root cause analysis, invites scrutiny, and aligns with leadership priorities. It also encourages creativity. When the team understands the problem deeply, they can discover better solutions.

“Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do, and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.” — General George S. Patton

Craft your problem and vision statements to be concise and high-signal. Align them with the executive team’s perspective. If there’s friction there, that’s good, it means you’re working toward real alignment.

Once the problem and vision are defined, create success criteria that articulate the measurable outcome you expect if the project works.

Use leading metrics wherever possible; signals that will shift quickly if you’re on the right path. These are what you’ll monitor post-launch to confirm the hypothesis.

Good success criteria:

- Increase sign-up conversion rate by 10% for click-through traffic from Google

- Reduce CI build time by 15% for the frontend test suite

- Increase CES scores by 1 point in the (ecomm) checkout funnel

The criteria are measurable and targeted, and the expected impact is achievable.

Poor success criteria, and why:

- Increase NPS score by 1 point

- NPS is lagging and easily influenced by unrelated factors

- Users are happier with our UI

- “Happiness” is vague and not easily measurable

- Reduce customer complaints by 30%

- Could lead to poor solutions, like making it harder to complain

Once the success criteria are in place, the shaping team can sketch possible solutions and define scopes. But here’s the key:

It’s the implementation team’s job to find the best path from problem to vision.

The success criteria give them the target. The scopes give them a starting point.

Project Scopes

Project scopes are a powerful tool for aligning expectations across the business. They give a clear view into what the shaping team believes will drive the most impact, and invite collaboration before the build begins.

Here’s how to read priority levels: P0: Must-do. Without this, the project fails. P1: Expected to happen, but could be dropped if needed. P2: Nice-to-have. Only happens if time allows.

This priority framework captures the “variable scope” side of fixed timeline work. It signals that the team will aim to complete as much as possible, but can shift focus based on what they learn along the way.

This autonomy is a major driver of team morale and momentum. It gives implementation teams ownership of outcomes, not just task lists.

Scopes strike a balance between direction and flexibility. They show intent while leaving room for interpretation and creativity.

A good scope is actionable but open-ended. For example:

“Send appointment reminders via email”

That scope invites clarifying questions:

“How often should reminders go out?” “Do we send one for every appointment type?”

These questions create opportunities for dialogue, refinement, and better outcomes.

The shaping team should come prepared with context, and stay open to change. If an engineer says,

“Data shows patients respond more to texts than email, should we switch focus?”

The right move is to reconsider the plan, not double down on the spec.

Designs

Designs are helpful, but the fidelity should match the team’s maturity and the complexity of the problem.

In the shaping phase, the goal isn’t to prescribe every detail. It’s to inspire the build, not restrict it.

- If your team struggles to visualize outcomes, high-fidelity designs can serve as strong references.

- If your team has a solid design system and deep domain knowledge, low-fidelity sketches — or even no designs — may be enough.

The real goal is to enable fast collaboration between designers and engineers during the build. Mature teams can prototype in real time, riffing on shared mental models instead of pixel-perfect mockups.

Eventually, teams should evolve past the waterfall rhythm of “design → handoff → build.” When they do, shaping becomes about direction and guardrails, not locked-down UI.

Ticket Creation

Fixed scope projects often begin with a bloated epic full of tickets, each one a pre-defined task handed down from the planning phase.

Fixed timeline projects work differently.

Tickets are created on demand, as the work unfolds. They’re a byproduct, not a starting point.

The goal isn’t to define every task up front. It’s to empower engineers to track and manage their work however they see fit. That might mean:

- Writing tickets to clarify dependencies

- Adding acceptance criteria for QA

- Skipping tickets entirely for low-overhead tasks

Every team is different. Let the ticketing system serve the work, not the other way around.

What Happens Next

This article focused on planning, not building. But when teams plan this way, here’s what you often see, within just a few days of starting:

- Engineers ask important questions, and have space to do it

- Teams rally around the highest-priority scopes

- New members find their role and rhythm

- People start pairing up to move faster

- Prototypes emerge

- Specs evolve

Timeboxing contains scope without killing creativity. Unlike artificial deadlines slapped on fixed-scope projects, fixed timelines give teams control. Teams adapt to hit the goal, not ship everything imaginable.

Managers shift their focus from process micromanagement to collaboration quality. Teams stay creative, aligned, and energized.

In many ways, putting smart people together with a great spec really is like planning a wedding. You set the stage, but some of the best parts are what you didn’t plan.

In the final segment of this series, I’ll share six years worth of lessons from real teams using this process in the wild: patterns, pitfalls, and pivots that made it work. Follow on LinkedIn to catch Part Three!